India’s Sedition Law Needs to Change

by Harsh Dubey \ March 29, 2018

Of the all the anachronistic, colonial-era sections of the Indian Penal Code, Section 124-A probably holds a special place in the long-decomposed hearts of Thomas Macaulay, Colonel Dyer and the like. It is perfectly representative of the extrajudicial excess particular to colonial repression: it is vague and therefore broadly applicable; it was created in response to fears of rebellion against the colonial state; and it ensures that convicted subjects spend substantial time in jail.

124A. Sedition.—Whoever, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, 102 [***] the Government established by law in 103 [India], [***] shall be punished with 104 [imprisonment for life], to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine.

(Fun fact: Thomas Macaulay, who drafted said law, famously decreed that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”)

A law like the Sedition Law should have been relegated to the annals of history the minute the tiranga was raised above the Red Fort. Instead, it has continued virtually unchanged in the Indian Penal Code, save a 1962 Supreme Court decree establishing incitement to violence as a necessary condition for its use.

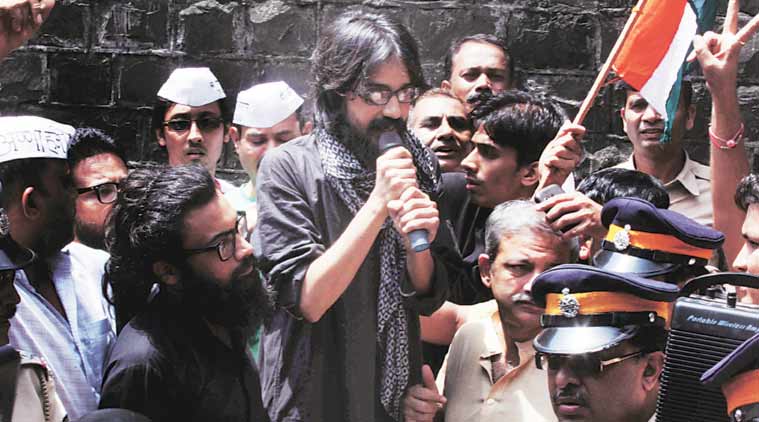

Why this is so isn’t entirely clear until one looks at the cases in which the law is (mis)applied. Sedition was used to justify the arrest of Aseem Trivedi for drawing anti-corruption cartoons in 2012. It was used to charge 60 Kashmiri students for cheering for Pakistan in a cricket match against India in 2014. It led to the arrest of Tamil folk singer S. Kovan for two songs that criticized the Tamil government’s state-owned liquor shops in 2015. Shockingly, sedition charges were even slapped on almost 9,000 people at once in Tamil Nadu for protesting a nuclear power plant.

Evidently, sedition law isn’t just about sedition – it’s a blanket law that the government can use to repress any activity it finds unsavoury. Moreover, the aim isn’t necessarily imprisonment. Charging someone with sedition is more like firing blanks than bullets – the aim is to intimidate, not necessarily harm. Dealing with police investigations, having a significant black mark on future employability, and suffering a tortuously slow and frustrating legal system are their very own sentence. Imprisonment is often secondary – that’s why sedition charges have been applied in so many cases of peaceful protest despite the incitement to violence requirement.

Such actions should have no place in a modern, liberal democracy like India. The very first sub-clause of Article 19 of the Constitution sets out the right to freedom of speech and expression, and sedition law is a violation of that principle. Yes, there is a provision for “reasonable restrictions.” However, to argue that any statement against the government should be restricted clearly does not fall into that category.

The only fix to this problem is to repeal section 124-A. Dissent is the lifeblood of a democracy, and so every time we slap sedition charges on a dissenter, we discourage the freedom of expression so carefully enshrined in our constitution.

Those in favor of keeping sedition law argue that it is necessary to keep control of terrorism and violent separatism. However, terrorism and freedom of speech are separate issues and to conflate the two is to do injustice to both. Those who claim that sedition law is necessary to combat terrorism ignore the Unlawful Activities Protection Act as well as a slew of other laws passed specifically for that purpose.

In this respect, perhaps we should take our cue from the United Kingdom, which repealed its sedition act in 2009. The UK Ministry of Justice noted that “these common law offences [UK libel and sedition law] are anachronistic and their continuing existence, albeit seldom used, has been cited by other countries as justification for the retention of similar laws, which have been actively used to restrict media freedom.” If our former colonizers can admit the absurdity of sedition laws of their creation, why are we so eager to keep them?

Harsh Dubey is a freshman at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service and a staff writer for India Ink.